Daily art story: Monet's Water Lilies

“I perhaps owe having become a painter to flowers.”

Claude Monet was born as Oscar-Claude Monet on November 14, 1840 in Paris. He was a founder of French Impressionist painting, and the most consistent and prolific practitioner of the movement's philosophy of expressing one's perceptions before nature, especially as applied to plein-air landscape painting. The term "Impressionism" is derived from the title of his painting “Impression, Sunrise”, which was exhibited in 1874 in the first of the independent exhibitions mounted by Monet and his associates as an alternative to the Salon de Paris.

Monet's ambition of documenting the French countryside led him to adopt a method of painting the same scene many times in order to capture the changing of light and the passing of the seasons. From 1883 Monet lived in Giverny, where he purchased a house and property, and began a vast landscaping project which included lily ponds that would become the subjects of his best-known works.

In 1899 he began painting the water lilies, first in vertical views with a Japanese bridge as a central feature, and later in the series of large-scale paintings that was to occupy him continuously for the next 20 years of his life. (Wikipedia)

The Water Lilies or Nymphéas series comprises approximately 250 oil paintings. Today, we’re enjoying some of the masterpieces from this series.

“My garden is my most beautiful masterpiece.”

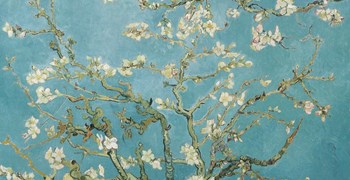

Monet moved to Giverny in 1883 and lived there until his death in 1926. On the grounds of his property he created a water garden 'for the purpose of cultivating aquatic plants', over which he built an arched bridge in the Japanese style.

In 1899, once the garden had matured, the painter undertook eighteen views of the motif under differing light conditions.

Claude Monet, Water Lilies and the Japanese bridge, 1897–99

Princeton University Art Museum

Surrounded by luxuriant foliage, the bridge is seen here from the pond itself, among an artful arrangement of reeds and willow leaves.

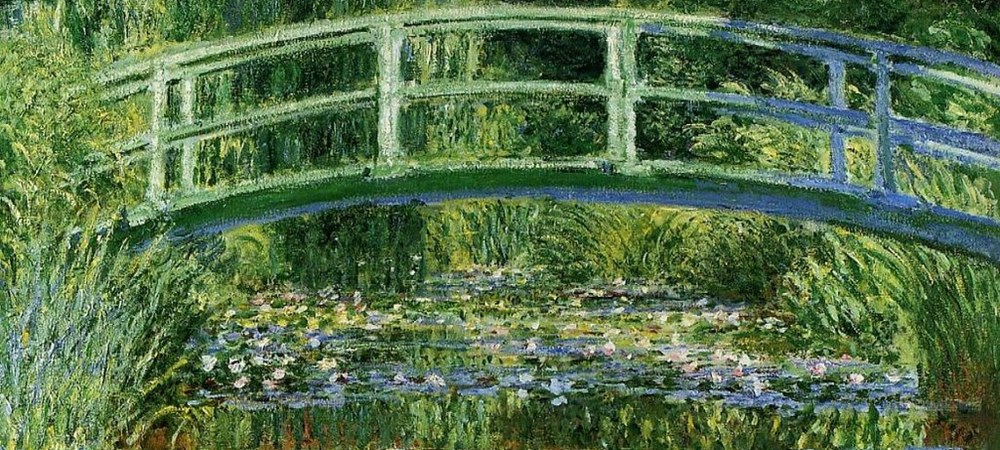

Claude Monet, Bridge over a Pond of Water Lilies, 1899

The Metropolitan Museum of Art: https://museu.ms/museum/details/570/the-metropolitan-museum-of-art

The vertical format of the picture, unusual in this series, gives prominence to the water lilies and their reflections on the pond.

“Everything I have earned has gone into these gardens.”

Monet, a passionate horticulturist, purchased the land, intending to build something "for the pleasure of the eye and also for motifs to paint."

During his final decades, he almost exclusively painted the garden filled with water lilies he had created there. The garden provided an infinity of motifs to be observed from various viewpoints and with a constantly changing play of light and reflections on the water's surface.

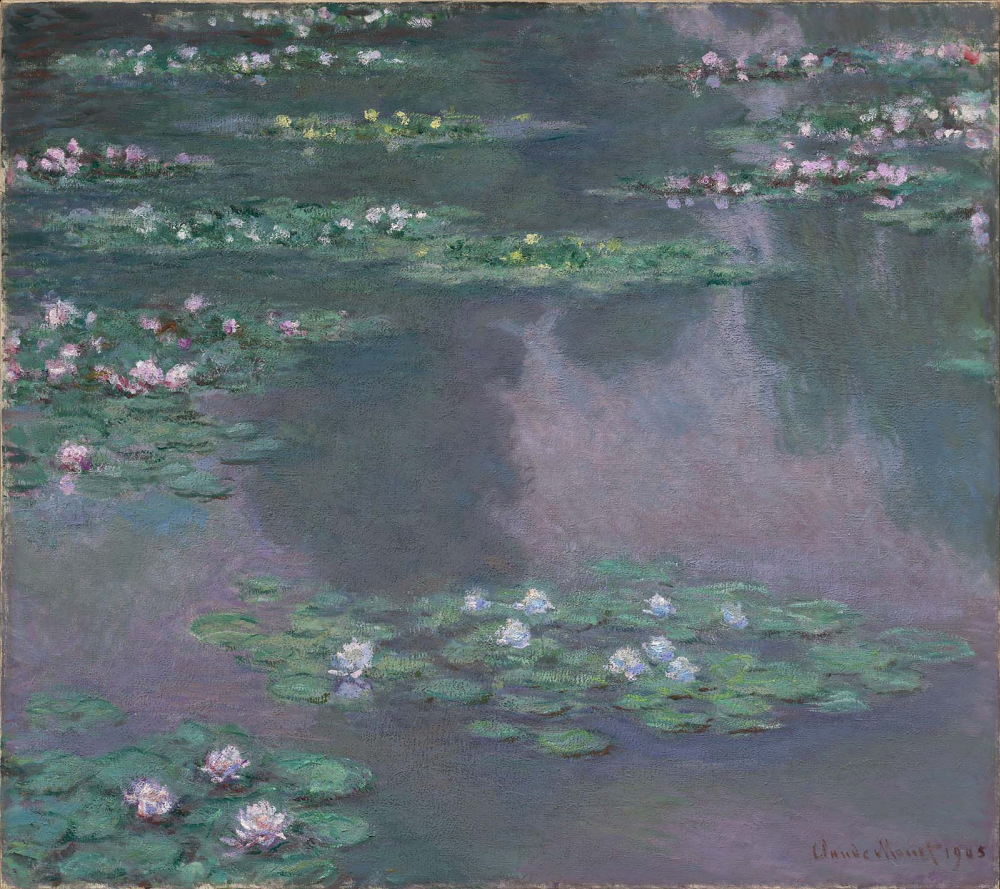

Claude Monet, Water Lilies, 1905

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston: https://museu.ms/museum/details/586/museum-of-fine-arts-boston

Here, the pads of lilies scattered across the painting suggest the water’s surface, receding into space. The pattern of light and dark beneath the lilies indicates the reflection on the water-sky and the trees on a distant bank. Monet exhibited forty-eight of these “landscapes of water” in 1909. Fascinated by the artist’s subtle fusion of reality and reflection, critics compared the paintings to poetry and music.

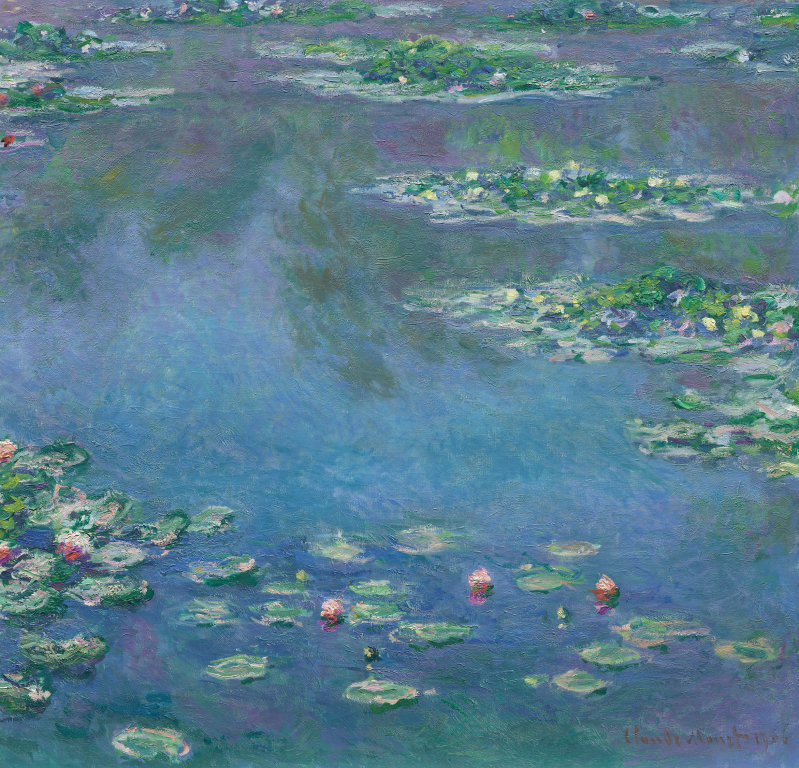

Claude Monet, Water Lilies, 1906

Art Institute of Chicago: https://museu.ms/museum/details/10101/the-art-institute-of-chicago

"One instant, one aspect of nature contains it all," said Claude Monet, referring to his late masterpieces, the water landscapes that he produced at his home in Giverny between 1897 and his death in 1926. These works replaced the varied contemporary subjects he had painted from the 1870s through the 1890s with a single, timeless motif—water lilies. The focal point of these paintings was the artist’s beloved flower garden, which featured a water garden and a smaller pond spanned by a Japanese footbridge. In his first water-lily series (1897–99), Monet painted the pond environment, with its water lilies, bridge, and trees neatly divided by a fixed horizon. Over time, the artist became less and less concerned with conventional pictorial space. By the time he painted Water Lilies, which comes from his third group of these works, he had dispensed with the horizon line altogether. In this spatially ambiguous canvas, the artist looked down, focusing solely on the surface of the pond, with its cluster of plants floating amidst the reflection of sky and trees. Monet thus created the image of a horizontal surface on a vertical one. Four years later, he further transcended the conventional boundaries of easel painting and began to make immense, unified compositions whose complex and densely painted surfaces seem to merge with the water. — Entry, Essential Guide, 2009, p. 232.

Claude Monet, Water Lilies, ca. 1914–1917

Legion of Honor Museum: https://museu.ms/museum/details/531/legion-of-honor-museum

Claude Monet, Nymphéas, ca. 1915

Musée Marmottan Monet: https://museu.ms/museum/details/709/marmottan-monet-museum

Claude Monet, Water Lilly Pond, 1917/19

Art Institute of Chicago: https://museu.ms/museum/details/10101/the-art-institute-of-chicago

During World War I, after several years of inactivity because of bad health and grief over the death of his second wife, Claude Monet embarked on a period of intense work. Building a large studio and improving his garden, he began a group of monumental paintings of water lilies that he would later offer to the French state. Alongside this project, he painted a suite of 19 smaller canvases, including the present one. There is evidence—including a few photographs of the artist working in his garden—that Monet conceived these paintings outdoors and then reworked them in his studio. By this last stage of his career, however, the distinction between observation and memory in his work is intangible, and perhaps even irrelevant.

“I’m good for nothing except painting and gardening.”

As age and deteriorating eyesight descended upon the artist his works lost almost all sense of form and are now referred to as "Abstract Impressionism". Cezanne once said that Monet was “only an eye, but my God, what an eye.” Monet died on December 5, 1926, nearly blind. He was known to have said that he “feared the dark more than death.” (Newsfinder)

The paintings are on display at museums all over the world, including the Musée Marmottan Monet and the Musée d'Orsay in Paris, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Saint Louis Art Museum, the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City, Missouri, the Carnegie Museum of Art, the National Museum of Wales, the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Nantes, the Cleveland Museum of Art, the Portland Art Museum and the Legion of Honor.

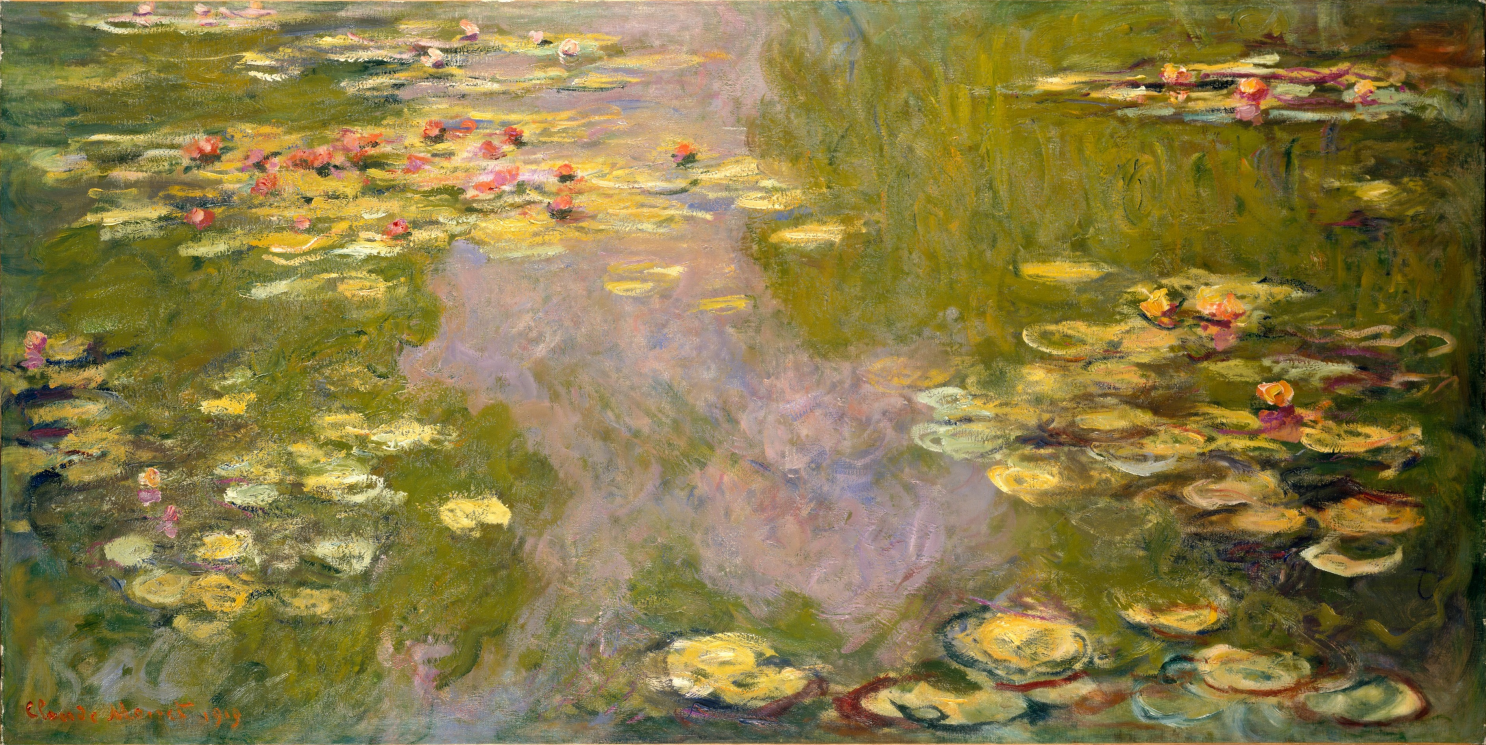

Claude Monet, Water Lilies, 1919

The Metropolitan Museum of Art: https://museu.ms/museum/details/570/the-metropolitan-museum-of-art

This work is one of four pictures of water lilies that, quite exceptionally, Monet finished, signed, and sold in 1919. Much of his late work was not finished, and few paintings were released for sale. In a letter he reported that he was not yet pleased with the paintings, but that he was working on them "with passion."